-

Warsaw: September 3-5

My Airbnb wasn’t quite ready, so I had coffee and a pastry at a little cafe around the corner. My flat was quite nice, within 5 minutes of the completely reconstructed Old Town, which was razed to the ground after the 1944 uprising by the Armia Krajowa AK, the Polish Home Army, which remained loyal to the London-based Polish government-in-exile and anti-communist. The AK was much larger and more effective than the French Resistance, but is not well known in the West. During the Warsaw Uprising beginning in August 1944, the AK recaptured much of Warsaw from the Wehrmacht in the hopes that the Soviet Army just across the Vistula would intervene to decisively defeat the Germans. Stalin cynically did nothing, and the Germans proceeded to crush the rebellion, reclaiming control in late September. Stalin sat by so that the Germans could defeat the AK, which Stalin saw as an armed impediment to his plan to install a post-war Soviet puppet state. The Germans eventually destroyed almost 85% of the city, including 100% of the historic center.

As in Gdánsk, the meticulous rebuilding of Warsaw was remarkable. Many of the pre-war buildings appeared as if they’d never been destroyed.

Syrenka mermaid in Old Town Square

Royal Castle 1619

Madame Curie house

Warsaw Ghetto line

Part of ghetto wall

Warsaw Uprising Monument We viewed a number of the key sites on the Old Town walking tour, which began at the King Sigismund Column. There is little remaining of the Warsaw Ghetto, which was utterly destroyed by SS General Jürgen Stroop, who was executed by the Poles after the war. Only a few ruins of the wall remain. The nearby monumental memorial of The Warsaw Uprising commemorates the millions of Poles who perished between 1939 and 1945, estimated at six million, including three million Polish Jews. Several hundred thousand Poles were also deported by Stalin to Siberia and Kazakhstan during this period with few reported returnees. I recommend Bloodlands by Yale professor Timothy Snyder for a well-documented history of the millions who perished under both Hitler and Stalin.

After the tour, I had a nice lunch just outside the Old Town and made my way into central Warsaw. I wanted to see the British Prudential building that had been Warsaw’s tallest pre-war building.

The rebuilt Prudential building

Central Warsaw

Newer Warsaw skyscrapers Central Warsaw is filled with modern towers and government buildings, including some from the communist era. Like other Eastern European cities, the streets were litter-free and there were no signs of homeless people.

I took a long route back to Old Town where I had a light dinner before heading back to the apartment. I noticed that the weather is Warsaw was warmer than in Kraków or Gdánsk. It must be caused by its interior location.

An urban park with the national colors

Memorial plaza on the site of the Warsaw Ghetto

The floodlit Royal Palace The next morning I booked a private “Communism Tour” in a restored Soviet-made Lada. My guide not only showed me sites related to the communist era; he also showed me some areas that were untouched by the war. After we visited the Field Cathedral of the Polish Army, a military church with a wing dedicated to the Katyń Massacre, he told me the story of the murder of pro-Solidarity priest Jerzy Popieluszko. He was kidnapped in 1984 by a branch of the SB secret police known as the “Shadow People”. He was beaten to death and hurled into a reservoir. His murder galvanized the anti-communist opposition and played a role in the dictatorship’s ultimate collapse.

More on the Katyń Massacre mentioned above—on September 17, 1939 the Red Army invaded Poland as part of the deal with Hitler and took thousands of Polish Army soldiers as prisoners. Many of the enlisted men were eventually released, but the officers were taken to a prison camp outside of Smolensk, in the Katyń Forest. After six months, Stalin and his NKVD secret police commissar, Beria, ordered the 22,000 officers liquidated, fearing that they could form the nucleus of a bourgeois opposition after the war. They were executed in the NKVD manner, with a bullet in the occipital nerve and then dumped into massive trenches, where their remains were bulldozed over. In 1943, advancing German units overran Smolensk and discovered the mass graves. They invited Polish officials and the Red Cross to view the site, but the Soviets lied and claimed that the Polish officers had been murdered by the Germans. The Western Allies reluctantly accepted Stalin’s lies until the truth was admitted in 1991. The Poles always knew that the Russians were responsible and have never forgiven them. Andrzej Wajda’s 2007 film Katyń is highly recommended viewing on regarding this atrocity.

One of the highlights of the tour was visiting the infamous 778’ tall Palace of Science and Culture, completed in 1955 in the Stalinist Social Realism style and proclaimed as a brotherly gift to their Polish comrades from the peace-loving peoples of the USSR! It was the backdrop for the stunning Polish Millennium military parade in 1966 that celebrated 1,000 years of Polish statehood and which was remarkably free of any communist regalia or symbolism. It’s worth a watch. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9c9IejeNxjU

Palace of Science and Culture

Palace entrance

Lazienki Palace

Royal Theater in Lazienki Park

Orangerie in Lazienki Park

Interior of the Field Cathedral

Katyń plaques

More Katyń plaques

Nave of garrison church The stately Lazienki Park features a number of neo-classical buildings, including an orangerie. The park was largely built during the reign of the last Polish king before the first partition of Poland in 1772, Stanisław August Poniatowski, who was also a lover of Catherine the Great of Russia. Lazienki Park was thankfully untouched by the war.

We ended the tour with a drive through the working-class Praga district on the right bank of the Vistula. Praga was the only section of Warsaw untouched by the war, besides Lazienki Park. Now it’s becoming a hipster area given its relatively low rents.

Since I had an early flight back to Seattle via Amsterdam the next morning, I stayed at the Marriott by the airport. I was happy to have an early dinner with an old friend from Orange County who, with his Polish wife and two daughters, had relocated to Warsaw. Even though he was born in Poland, he expressed frustration with the bureaucracy and suggested that they might return to the US.

And so ended my six-week journey through the Balkans, Ukraine and Poland, the longest foreign trip of my life. I’ll write up my 2019 trips to Mexico City and Eastern Europe next, with occasional forays into a series of essays which friends are urging me to post. I hope you’ve enjoyed the blog so far and I look forward to sharing more of my adventures and essays with you.

-

Gdánsk: August 31 to September 3, 2018

My spacious and airy Airbnb was centrally located in an old apartment building. After completing my self check-in, I trudged up 3 flights of stairs to my apartment just behind a German couple returning to their unit. They invited me in for drinks and suggested several restaurants. I enjoyed their company and was disappointed that they were leaving the following day.

The next morning, September 1st, was the 79th anniversary of the beginning of World War II. At the time Gdánsk was the German Free State of Danzig, an ancient member of the Hanseatic League. German overland access to Danzig was one of Hitler’s demands to Poland. Later that day, I would come across a memorial service marking the invasion of Poland.

My spacious apartment

St Mary’s Basilica from my window

St Mary’s Basilica 14th c.

Leafy side street

Harbor view

Klatka-great breakfast spot I enjoyed the outdoor breakfast so much at Klatka that I returned every morning. After breakfast I strolled around the harbor area and walked into St. Mary’s Basilica. It’s important to understand that the Red Army nearly razed Gdánsk to the ground after capturing it from the Germans in March 1945 before handing it over to the Poles. The Poles painstakingly rebuilt the entire historic core based on old architectural drawings and photographs. The majestic churches, therefore, have no stained glass windows and much of the interiors were lost. Considering how relatively poor Poland was under 40 years of communist rule, the restoration is remarkable.

Around noon, I joined a walking tour of the old town with our enthusiastic guide, who was clearly in love with his city. Walking around the old town was wonderful. One can see how prosperous this old port city was in the past. There were also several shops selling amber, for which this part of Poland is famous. The Polish word for amber is bursztyn, or “burning stone”. I realized then that many surnames in the US, like Burstyn and Bernstein, derive from the name of this gemstone of fossilized tree resin.

16th c. Upland Gate, main entrance to Old Town

The town hall in the distance

The Golden Gate (Złota Brama)

A rear view of the basilica

Baroque municipal office

The town hall The walking tour ended at the Post Office, where our guide pointed out the bullet holes in the wall surrounding the garden behind the post office. Although Danzig was a German Free State, the Versailles Treaty gave Poland control of the post office and customs. The war came to Gdánsk when the German battle cruiser Schleswig-Holstein opened fire on the Polish base at Westerplatte. Shortly afterwards, a German militia group attacked the post office and executed a number of postal workers in the garden.

The Post Office

Execution site outside

Memorial service at the Post Office

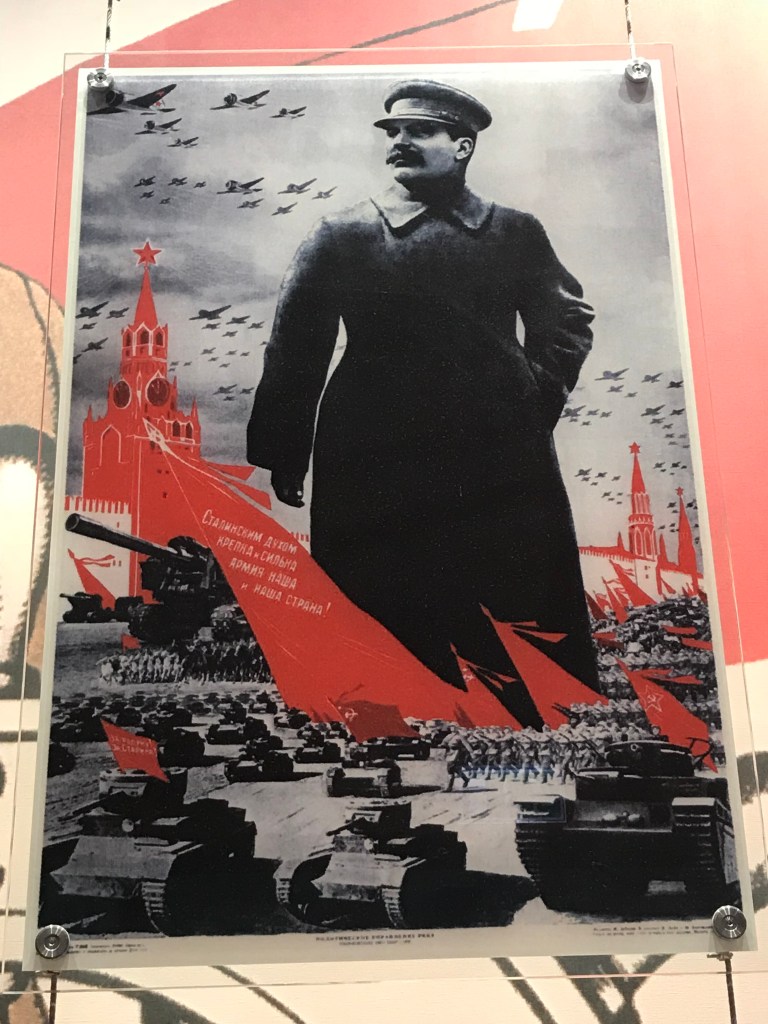

Young Poles dressed in period uniforms at the memorial service After watching part of the solemn commemoration, I walked over to the highly-recommended World War II museum and spent several hours wandering through the remarkable galleries. There was a large collection of Soviet and Fascist poster art, which I found fascinating.

The WW2 Museum

Deportations

Katyn memories

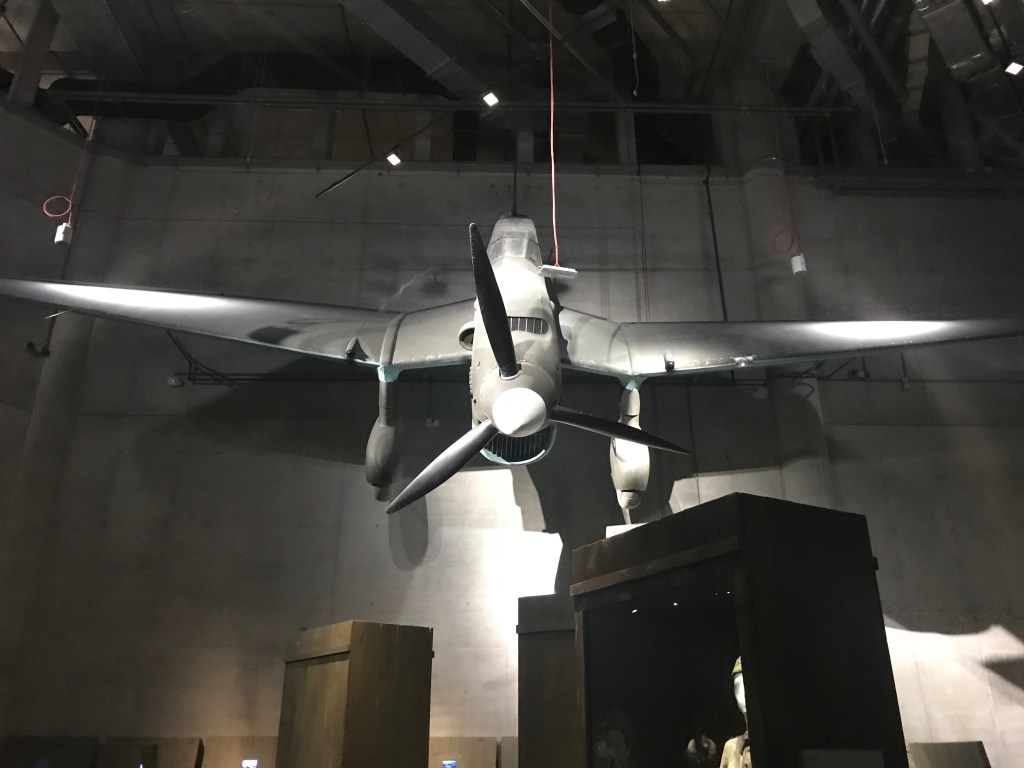

Stuka of the Luftwaffe

Italian Fascist poster

Late 30’s VW ad

The Red Tsar Stalin

Soviet propaganda

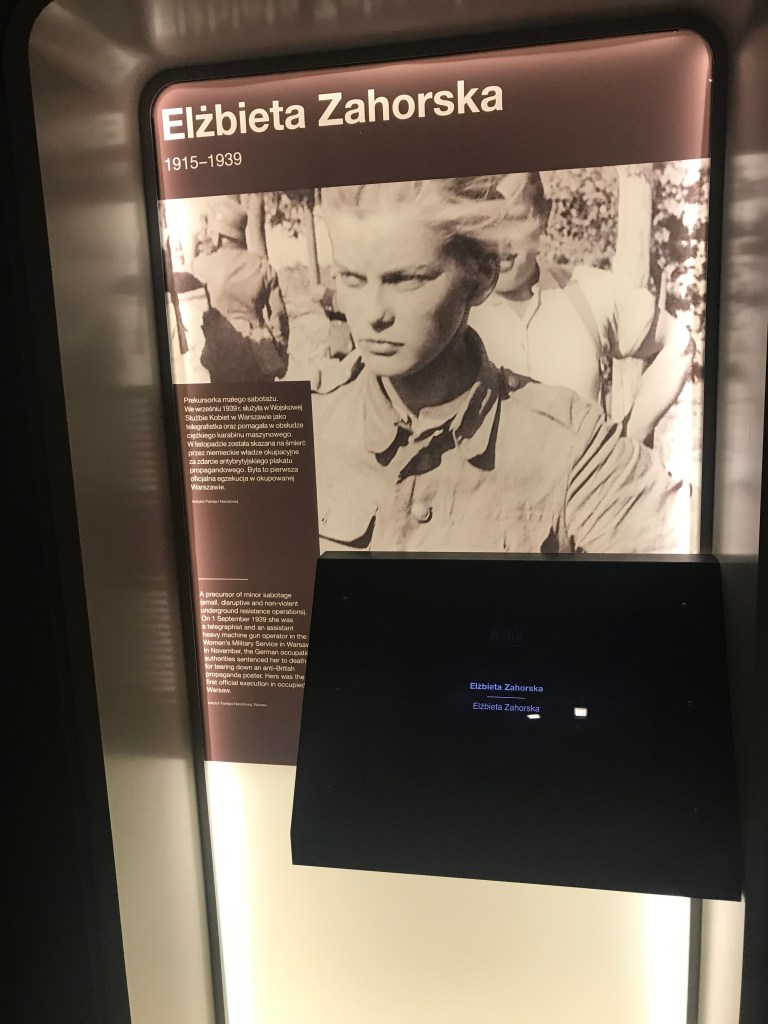

Polish woman in the AK Home Army executed by the SS From the museum, I walked a kilometer to the site of the famous Lenin Shipyards, where iron worker Lech Wałesa launched his mass Solidarność (Solidarity) movement in opposition to the communist dictatorship. After nine hard years, Solidarity finally prevailed when the communist state collapsed in early 1989. Wałesa was then elected the first president of free Poland.

Solidarność Memorial

Memorial close-up

Entrance to former Lenin Shipyard That evening I went to an “underground” cocktail lounge recommended by our tour guide. It wasn’t too crowded and I enjoyed a few drinks and charcuterie with some locals, who suggested I rent a bike and ride out to the Baltic Sea resort of Sopot the next day, which was predicted to be sunny and mild.

It was a bit of a hassle renting the bike by the main train station. The owner showed up after I waited for a half hour; but finally I was on my way to Sopot.

The route northwest to Sopot wound through some impressive city parks and broad boulevards and took about 45 minutes. Sopot has been a getaway for centuries and was a famous spa in the 19th and first half of the 20th century before going into a slumber during the communist period. It was Germanicized after the partition of Poland in the 18th century and remained so until the end of WW2. It has the longest boardwalk in Europe, a number of restored spas and villas, and beautiful white sand beaches, surrounded by conifer forests.

Sopot boardwalk

Beach on the Baltic Sea

Communist-era housing block seen on the way back from Sopot

Promontory at Sopot That night I went to a vegan restaurant outside of the old town for a much needed break from the heavy Polish cuisine. The food was excellent and the walk back at dusk was pleasant. I looked forward to a quiet night at the apartment before my flight to Warsaw the next morning. I was quite pleased to have added Gdánsk to my Polish itinerary.

-

Kraków: August 28-31

My Airbnb was perfectly located in Kraków’s Stare Miasto, or Old Town, a two-minute walk from Market Square and the iconic Gothic St Mary’s Basilica.

Market Square with St Mary’s Basilica and the Cloth Hall The square was full of tourists but not nearly as packed as other cities like Prague or Vienna. I had a snack and a glass of wine before joining an Old Town tour in the late afternoon. It was a large group with a fair number of British tourists, some of whom were drunk. We visited the main sites around the square and walked through Jagiellonian University, founded in 1364 by King Casimir II the Great. There’s a famous scene in the Polish film Katyń in which an SS general informs the faculty that the university is to be closed indefinitely after which many professors are arrested and deported to German concentration camps. The other famous movie filmed in Kraków is Schindler’s List.

Kraków dates back to the 7th century and was the capital of Poland until 1596. Interestingly, it was also the seat of the German General Government from 1939 to 1944 under Dr Hans Frank, the Nazi Governor General. Frank ruled from the famous Wawel Castle, on the Vistula River. Most readers are aware that the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp was built in a western suburb, which has become a major, if depressing, tourist destination.

View of St Mary’s from my Airbnb

St Mary’s Basilica

The nave of the basilica

St Barbara’s Church, late 14th c. Jesuit

The 14th c. Town Hall

Romanesque St Andrew’s Church late 11th c. Kraków, like Prague, wasn’t destroyed in either of the world wars, so many ancient churches and castles are still intact and in pristine condition. I spent a few weeks in Prague in September 2001 and feel that Kraków is just as impressive.

I decided to eat dinner at the cafe in my building and had a nice chat with the bartender about Kraków who offered suggestions for offbeat destinations, so I decided that I’d visit the salt mines and Nova Huta towards the end of my visit on his recommendation.

After a great night’s sleep, I had some coffee and yogurt in the apartment and took a long walk through Old Town to pick up a rental bike. The woman at the shop was helpful and gave me a cycling map. I also rented an iPhone holder so I could follow my route without trying to look at the map. I headed out through the city and suburbs towards Auschwitz, although I didn’t visit since I didn’t have reservations and wasn’t sure what to do with the rental bike. The bike lanes were well marked and I was surprised by the size of Kraków outside of the historic core. There were also a number of parks. After my ride out to the western suburbs, I headed back along the bike trail to view Wawel Castle and the former Jewish quarter. The castle was magnificent and contained its own cathedral and massive ramparts. The Vistula is broad and makes for a beautiful riverfront ride or walk.

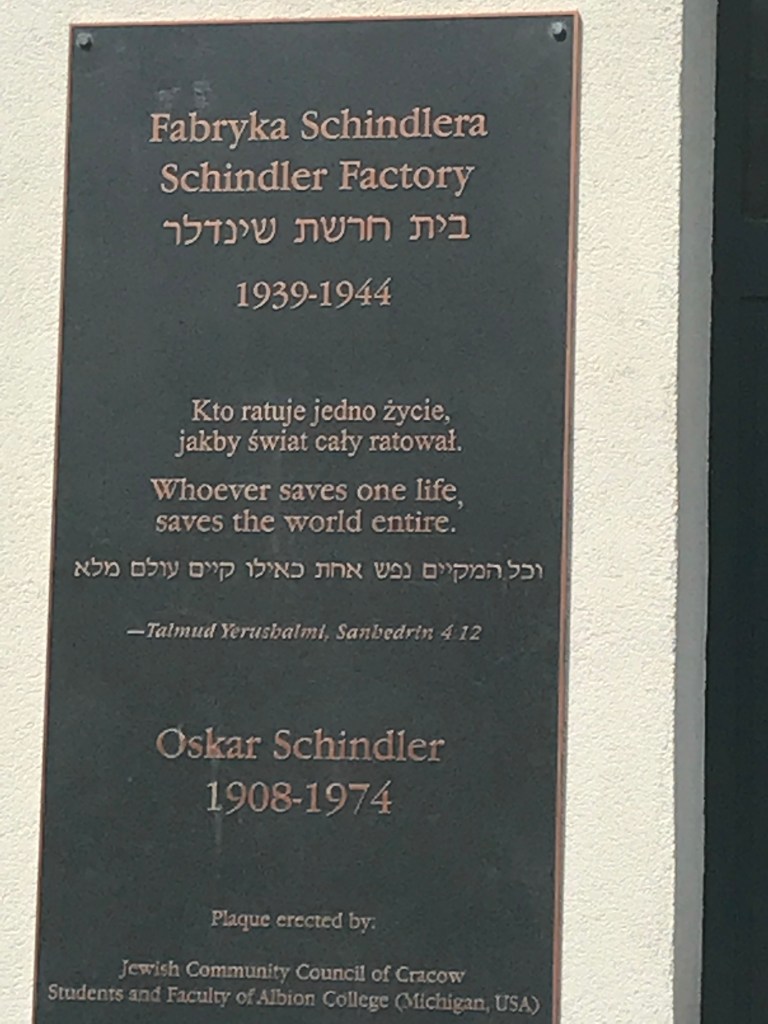

The ghetto was interesting, although perhaps to the chagrin of its survivors it is undergoing gentrification and is becoming a hip neighborhood. From my bike I saw quite elderly tour groups walking through the ghetto neighborhoods. It was a lachrymose scene on a beautiful sun-filled day. I drove by the Schindler Factory but the line was long and I was eager to try out a hip outdoor restaurant nearby for a late lunch.

Wawel Castle on the Vistula

Wawel tower

Wawel Cathedral in the castle complex

Looking up at Wawel Hill

The Vistula near the castle

Schindler plaque I booked a spot on the Kraków Dark History evening walking tour that night, which was excellent. The atmospheric city center takes on an even more impressive aspect when viewed at night. Our guide showed us where famous murders and other scandals had occurred over the centuries and pointed out haunted buildings and cemeteries.

Soprano singing Mozart inside the university grounds

Church of SS Peter and Paul within the university. Early 17th c. Baroque

St Andrew’s Church at night

University faculty near St Andrew’s

Market Square with Cloth Hall lit up at night The next morning I booked a tour of the Wieliczka salt mines, an hour outside of Kraków. Our guide drove us out in a Mercedes Sprinter which was quite comfortable. The mine is immense and was worked for centuries. It even contains a basilica and dormitories. The air was quite cool and refreshing. The full tour lasted almost three hours and involved a significant amount of stair-climbing, making for a good cardio workout.

Spooky passageway in the depths of the salt mines That night I treated myself to dinner at Pod Aniolami in Old Town, which was billed as traditional Polish cuisine with a French flair. It wasn’t that busy, so I felt like a mob boss sitting at an elegant table with my own private waiter. The food was superb as was the Burgundy. My waiter said that it’s packed during the tourist season. I went for a 5k walk around Old Town afterwards before heading back to the Airbnb for the night.

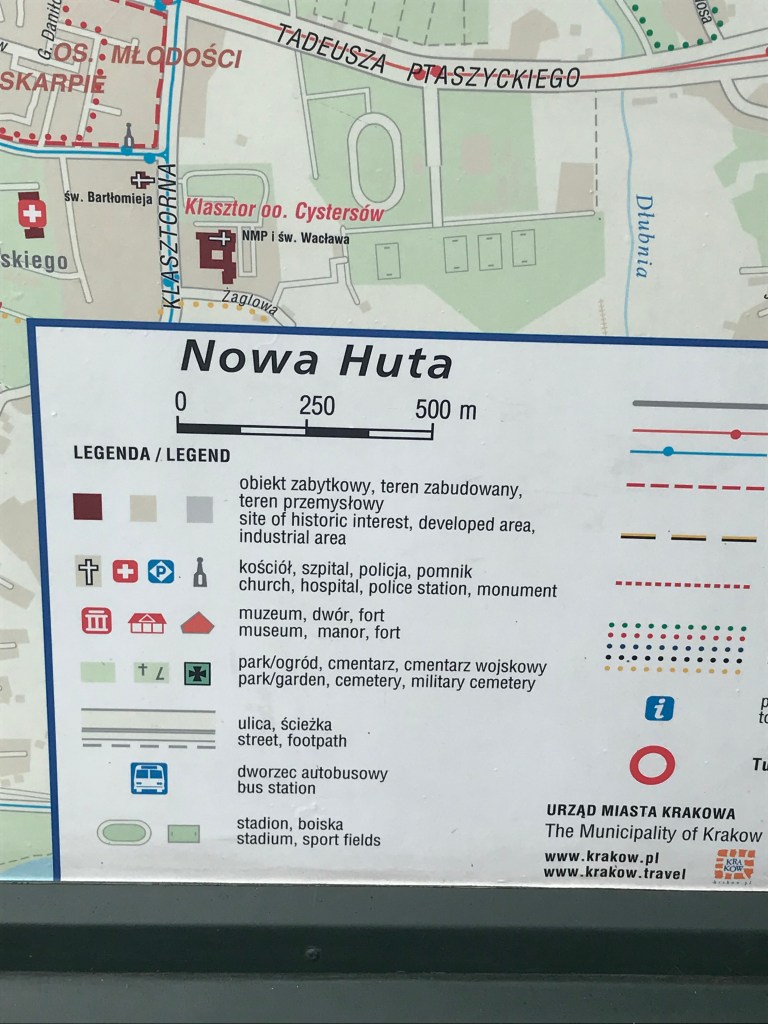

The next morning I found a hip breakfast spot on the other side of Old Town that served excellent coffee and food. After breakfast, I hailed a taxi to take me out to Nova Huta, the master-planned Communist city on the eastern edge of Kraków.

After the Communists solidified their power in 1948, they turned Poland into a totalitarian police state. The new regime looked on Kraków with suspicion, given the city’s long bourgeois past and palpable distaste for communism. In many ways, the new rulers represented the formerly rejected part of the population, so they were seething with resentment against traditional society and some felt that they built the vast Socialist Realist suburb to introduce a proletarian aspect to this genteel city.

Nova Huta means New Steelworks in Polish and was the site of the Vladimir Lenin Steelworks as well as a giant cigarette factory. Most of its 50,000 residents were brought in from other parts of rural Poland, so they held no allegiance to Kraków. I actually find the Stalinist architectural style impressive, if a bit dehumanizing. Any fan of this style will be in heaven in Nova Huta, with its broad boulevards and massive housing blocks.

The steelworks have long been dismantled and Nova Huta is becoming a gentrified area for young professionals, although in the 1990’s it was a dangerous drug-infested slum.

After checking out, I grabbed an Uber to the airport for my late afternoon flight to Gdánsk. My young driver told me that he was studying computer science and had a Ukrainian girlfriend, stating that Polish girls were snobby. I chuckled at that. He told me that over 600,000 Ukrainians were living in Poland in 2018 and that they were smarter and more ambitious than his fellow Poles. Of course now there are almost two million Ukrainians living in Poland because of the war. The Ukrainians assimilate more easily to Polish culture than other immigrants since they are fellow Slavs and speak a somewhat similar tongue, although the alphabet is different. One always gains interesting perspectives from drivers!

-

Lviv

I found a decent coffee place on Market Square and had a cappuccino and a Lviv Croissant, which is an unlikely Ukrainian chain. I had some time to kill before the first walking tour, so I caught up on emails and texts.

As I headed to the morning tour meeting spot, I noticed two unmistakable LDS missionaries. They were from Idaho and when I asked them about the success of their mission, they frowned and reported that while most of the Ukrainians with whom they spoke professed to believe in God, they were not at all receptive to their message. I said “good luck” and left before they started working on me!

The morning tour was really informative. As I’ve reported in previous posts, it’s amazing that so many old towns, though in various states of shabbiness or restoration, survived the antinomian impulses of the Soviets.

I struck up a conversation with an older New Yorker who had lived in Lviv as a child, but was able to flee in the early fifties. He and his wife and daughter were investigating their Jewish roots and he told me that he recognized several of the old churches and temples from his childhood. The Soviets stored horses in one old synagogue. It was amusing when his wife scolded him for talking during the guide’s presentation.

We all had lunch at an old cafe and shared the usual foreign tourist banter. A younger French couple were particularly amusing.

Armenian Orthodox Cathedral late 14th c.

Church of the Holy Spirit 1729

Mannerist Chapel of the Boim Family. Early 17th c.

1930’s Jugendstil

Art Nouveau block

Interior of Armenian Cathedral After lunch I did a little shopping on Market Square and also walked into the opera house to see the restored stage.

The afternoon architecture tour was led by a recent graduate of the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv. We were joined by a Dutch couple and a very quiet middle-aged American who claimed to work for the Peace Corps. Our guide was very entertaining and he and I hit it off. Like many of the Eastern Europeans whom I met on this trip, he wasn’t afraid to hide his opinions. He was strongly anti-Russian.

We were impressed with the number and variety of buildings surviving the two world wars and fifty years of Soviet misrule. Some dated to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and many others from the Austrian period beginning in 1772.

Our guide

General Kulchitsky statue. Bringer of coffee to Lviv

Benedictine Monastery early 18th c.

Pre WW2 Yiddish hat shop

Another view of the hat shop

St John Baptist mid-13th c.

St Nicholas Church. Oldest building in Lviv 13th c.

St George slaying the dragon

Secessionist-style synagogue During recent restoration, advertisements in Yiddish for a men’s hat shop were revealed (above). They’re finding all sorts of architectural gems under decades of cheap Soviet paint and stucco.

The Ivan Franko National University, formerly the University of Lviv, was founded by royal charter in 1661 and was run by the Jesuits. It was the second oldest university in the Commonwealth after Kraków’s Jagiellonian University. Ivan Franco was a renowned Ukrainian scholar in the 19th century and the university was renamed after him upon the collapse of the USSR. It was a center of the Ukrainian intellectual renaissance under the tolerant Austrian rule.

Entrance to the university

Allegorical statue of Science on university facade

Another view of the main building in Viennese Renaissance style

Allegorical statue of Love

University street scene

Ivan Franko

The group in front of a Secessionist-style building

Monument to the Virgin Mary

Polish-EU border crossing Since it wasn’t convenient to fly from Lviv to Kraków without backtracking east to Kyiv, I decided to use the driver service that I’d used in Bulgaria-mydaytrip.com

After an excellent breakfast the next morning, I packed up and checked out of the Airbnb and met my young Polish driver, Michał, right on time in his white Audi A3 wagon, the same model as in Sofia. He told me he had never been across the border to Ukraine and was nervous, which surprised me since Lviv looks like a somewhat prosperous Central European city. He was also worried about the border wait, but we were through in less than 20 minutes. He was relieved to be back in Poland and proudly contrasted the modern freeway with the two-lane highway in Poland. He also told me, unbidden, about some obnoxious Americans he had driven around Poland earlier in the week. I laughed and said that I hoped I didn’t fall into that category.

The drive to my Airbnb in Kraków’s Old Town was less that 4 hours and he was an enjoyable companion so I gave him a hefty tip. As a hard-working new father, I was happy to help out since the drive itself was faster and cheaper than going by plane.

-

Kyiv to Lviv: August 26, 2018

On Sunday morning I met up with the bike tour folks for our postponed bike tour of the Trukhaniv Island in the Dnipro and other riverside sites. I dropped by McDonald’s beforehand for breakfast since nothing was open. It was fine. I hadn’t been to one in 25 years.

We started our ride near Mariinskyi Park, which connects to the bike trails heading down the deep banks to the Dnipro bridges. The park was built as part of the Mariinskyi Palace, which was built for Empress Marie, the wife of Tsar Alexander II. From there we descended to the Dnipro and crossed the pedestrian/bike-only Park Bridge over to Trukhaniv Island, which is quite large and unspoiled and is a popular beach and picnic site for Kyivans and tourists. It’s pretty unspoiled and my guide had trouble keeping up with me as I tore across the gravel towards one of the beaches.

View of Kyiv from the Park Bridge

In front of Mariinskyi Palace

Semi-rural Trukhaniv Island

Ilya Muromets Memorial We stopped at the massive Ilya Muromets Memorial, which had just been dedicated three weeks earlier. He was a famous warrior of the Kyivan Rus’.

When I got back to the hotel I checked out and bade farewell to the lovely receptionist. She expressed her hope that someday soon Ukraine would be a prosperous democracy so that her children could thrive. I somehow elicit these hopeful comments while traveling. My sad-faced driver took me back to Boryspil Airport for the short flight to Lviv.

From Lviv Airport I grabbed an Uber to my exquisite Airbnb right on Svobody (Freedom) Avenue in the heart of Lviv. Before 1939, Lviv, then known as Lwow, was part of the Second Polish Republic. Stalin grabbed it after he and Hitler partitioned Poland in late 1939. People often forget that Hitler and Stalin were allies for almost two years before the German invasion of the USSR on June 22, 1941.

Before 1918 Lviv, also know as Lemberg, had been part of the Austrian Crown Lands, and the Austrian influence is widely visible in the architecture. My Airbnb was right across from the Lviv National Opera, a neo-Baroque theater built by the Austrians at the end of the 19th century.

Before the first partition of Poland, which was divided up by Catherine the Great of Russia, Frederick the Great of Prussia and the Austrian Hapsburg emperor, Lviv had long been part of the powerful Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which ruled a vast area of Eastern Europe for centuries. It was so powerful that the then-Pope christened it The Bulwark of Christendom.

The Commonwealth long ruled what is known as Right Bank Ukraine, which is the area west of the Dnipro. The Ukrainians had a love/hate relationship with the Poles, and had several uprisings against them. One of the legacies from the Commonwealth era is the Uniate Church, which is unique in that is has an Orthodox liturgy and a married priesthood, but is under the authority of the Pope.

Under the more liberal Austrians, Lviv became a center of the Ukrainian revival and its language was restored. It became the thriving capital of Galicia, and its population was divided equally among Poles, Ukrainians and Jews, with a small Armenian community. Stalin sent thousands of Poles to Siberia or forced them back to Poland, while the Jews were largely sent to the Nazi concentration camps. Stalin wanted Lviv to be a Ukrainian city, and so it remains.

Lviv is perhaps the most nationalistic city in Ukraine and its inhabitants speak Ukrainian overwhelmingly. In the US, immigrants from Galicia were known as Ruthenians, and many settled in the Pennsylvania coal and steel regions. A significant number emigrated to the Canadian Prairie Provinces and established prosperous wheat farms.

Stunning Airbnb

Steps to the sleeping area

View from the living room

Market Square from my Airbnb

Lviv National Theater

Typical old town street scene with classic tram The historic core is really atmospheric, like Prague. Wandering around the streets after a cooling rain generated an appetite, so I walked back to Market Square and had an excellent meal at Centaur, located inside a 16th century building. During the long trip through Eastern and Central Europe in 2018, I often consulted http://www.theculturetrip.com for restaurant suggestions. They’re usually spot on.

I had a drink at the bar next door and had a nice conversation with a Swedish couple before heading back to the apartment. I’d booked two walking tours for the next day and looked forward to a restful sleep.

-

Chornobyl

Dark Tourism has always fascinated me, and the prospect of visiting Chornobyl (Chornobyl is the Ukrainian word; Chernobyl is the Russian) was too enticing to pass up, so I signed up for a tour a month before. Most readers are familiar with this nuclear catastrophe from watching the acclaimed HBO series, which was based on the book Midnight in Chernobyl. When I told Ukrainians that I was taking the tour, they paled. Their memories of the disaster were such that it was the last place they’d want to visit.

The bus left from the main train station and I was one of the last to board. Finding the bus was a bit confusing. I sat next to a young German who worked for an NGO. His parents were seated in the seats across the aisle from us. The trip took about two hours on a two-lane highway and we passed through a few forest settlements on the way. I was struck by the ornate Orthodox churches looming above crude wooden houses.

We arrived at the military checkpoint at the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone, which was set up by the USSR in April 1986 and which encompasses a circular region of 30 km from the site of the Reactor 4 explosion. We were required to wear long pants and long shirts. Once we passed through the checkpoint, our first stop was at an uninhabited village about 20 km from the site. The majority of the visitors were Germans, and a couple of guys ventured a little beyond the approved path. Our guides were two Kyiv university students, Viktor and Olena. They issued FLIR radiation detectors which measured levels in millisieverts.

The photos below are from the first stop, the ghost town Kopachi.

The next stop was the immense Soviet Duga ICBM detection radar facility, which is 150 meters high and over 700 meters in length.

When we got to the main attraction, Viktor pointed out the enormous new steel dome funded by the EU and the USA to cover the Soviet-era concrete sarcophagus that had been formed by dropping immense amounts of concrete from Soviet military helicopters. Views of the new dome and the reactor, with the Soviet statue of Prometheus. The Soviets had a fascination with Greek mythology.

Close-up of the dome

The new dome

The cooling pond After passing the plant, we entered the abandoned city of Pripyat, which housed over 40,000 employees of the Chernobyl Atomic Power plant. By Soviet standards, this was a deluxe new city, with large flats, a well-stocked supermarket and theaters and parks. The famous amusement park and football field were scheduled to open on May Day 1986, a week after the disaster. It housed the Soviet elite-engineers, physicists and party luminaries. The forest has completely encroached on the city, and the football field is now a new growth forest. After Gorbachev declared the mandatory evacuation of Pripyat, 40,000 residents were commanded to pack for a weekend and boarded over 1,000 buses for Kyiv and Minsk. The evacuation was completed in under three hours.

Statue of Prometheus

Monument to the Liquidators

Apartment block

Football field

Close-up of stands

The football field

The iconic Ferris Wheel

Bumper cars

The shopping mall

The Hotel Polissya where the post-disaster command post was set up We were warned to stay on the marked paths, since large areas of the city are still radioactive. The silence was eerie and everyone spoke in hushed tones.

Once the Soviet government acknowledged the scale of the disaster, they moved quickly to safeguard Ukraine and Belarus from the potential nightmare scenario, including the poisoning of the Dnipro, which provided water to millions of citizens. They mobilized 500,000 “liquidators”. The paths we traveled on were the result of the excavation of 3 meters of roadbed and its replacement with new soil and asphalt. The excavated dirt and all other contaminated items, including vehicles and all household furnishings and food, were buried in other areas of the exclusion zone. Red Army marksmen were assigned to exterminate all escaped pets and other wildlife. Ironically, during the initial failed offensive to take Kyiv in the opening weeks of the 2022 Russo-Ukrainian War, the Russian army sent armored units into the most highly contaminated sectors of the zone, including the notorious Red Forest, which led to the evacuation of hundreds of soldiers with radiation sickness. Russian denialism at its best.

The Red Forest from the bus

Radiation warning signs near the Red Forest As we left the city, we passed by the actual village of Chornobyl, which houses the employees involved in the decommissioning of the atomic power plant. We had to pass through a radiation detection device before boarding the bus for the journey home. I registered 3 millisieverts, about the radiation level incurred during a one-hour airplane trip.

We arrived at the Kyiv train station after a two-hour ride and I was able to hail a cab back to my hotel immediately. I ate dinner at a good Georgian restaurant around the corner from the hotel and was eager to sleep after such a sobering day.

-

Kyiv: August 23 to 26

I boarded my flight to Kyiv on Ukraine International Airlines and was seated next to a younger Israeli woman who was headed to Kyiv for a business assignment. Like me, she was on her visit to Ukraine, and we commented approvingly on the efficiency of the passport control process at Boryspil Airport. My hotel sent a driver to pick me up for the drive into the heart of Kyiv. He was a sad fellow, who related that he’d come to Kyiv from the Donbas to flee the Russians.

The drive west from the main airport was on an eight-lane freeway that passed some large residential towers under construction and then crossed the wide Dnipro River into the city center. The hotel was tucked into a small alley behind the main boulevard, Khreshchatyk Street, and just a short stroll from the famous Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Freedom Square), the site of the bloody 2004 and 2014 color revolutions. The reception folks at the Crystal Hotel were lovely and my room was well-appointed and very quiet.

Right around the corner were some attractive restaurants, so I grabbed an outside table and ordered a big salad and a glass of Georgian red. A couple sat next to me who turned out to be a Canadian Embassy staffer and his lovely Ukrainian wife. I spilled a little wine on my jeans and asked the server to bring some soda water, but the Ukrainian woman poured a little salt on the stain, which happened to be on my right quad, and dabbed at it. The salt worked; however, I was surprised by the intimate gesture. She told me that if I met a Ukrainian or Russian woman, I’d stay in Kyiv. Her Canadian husband agreed, and told me that he far preferred Kyiv to Canada for a number of reasons and suggested that his comments would cause him trouble if known to his employer.

View from my dinner table

Preparations for Independence Day

Khreshchatyk Street The hotel receptionist told me that she had a special pass for me so that I could grab a good spot to watch the next day’s big military parade. After a good night’s sleep and a coffee, I wandered around the corner and passed through security and presented my passport and found a great place to stand just a hundred meters from the tribunal on the Maidan. I chatted with some young Ukrainians who had pictures of the berets denoting the regiments that would be marching by. Many of the units were fighting on the eastern Donbas front. In 2022, many Westerners forget that Ukraine and Russia have been at war since 2014.

Finally, the moving national anthem was played. Then the current president, Petro Poroshenko, gave a speech and then presented decorations to soldiers serving in the Donbas. I noticed the band played the old German hymn Ich Hatt’ Einen Kameraden during the presentation ceremony.

The other notable sight was the presence of Ukrainian Orthodox priests blessing the formations. The whole parade structure was similar to Russian and Soviet military parades, which makes sense given Ukraine’s long history as part of both.

Independence Day Parade Infantry Battalion National Guard in blue Armored units SU-35 flyover It was quite an experience watching such a massive military parade, the first I’d seen since the Bastille Day parade in Paris in 1997. There were units from Poland, Romania, Georgia, Lithuania, the UK, Canada and the US. I learned that Polish President Andrejz Duda and US Defense Secretary Mattis were also present.

After the parade, I was to meet a woman who was a friend of my Croatian acquaintance. I asked her to meet me in the lobby of the hotel and we then went to lunch. She was a political activist and had participated in the 2014 Maidan revolt, the Revolution of Dignity. Her assessment of the political situation in Ukraine was enlightening. After lunch, she asked if I’d like to meet a volunteer soldier for a coffee and we headed across the Maidan to a cafe. Her friend was a Polish volunteer and had just returned from the Donbas, where he was serving with a volunteer regiment that would become legendary in the 2022 Russo-Ukrainian war. He said the combat was sporadic but intense and that regular Russian Army troops were active participants. After parting, I walked around the Maidan and looked at the various posters celebrating the lives of Ukrainian patriots including Bogdan Khmelnystky, Symon Petliura, the leader of the Ukrainian People’s Republic after 1917, and the controversial Stepan Bandera, who fought against the Soviets during WW2 but who is accused of being a Fascist, especially by the Russians who condemn virtually all Ukrainians that way.

I had booked a bike tour of Kyiv that afternoon, but the guide had to postpone it until Sunday because of the security cordon around part of our proposed route. I walked a few miles around the surprisingly green city before grabbing a light dinner. I had booked a day trip to Chornobyl the following day, so I wanted to get a good night’s sleep.

-

A Visit to Transylvania

I’d booked a first-class passage on the CFR Calatori train to Brasov, in Transylvania. Romania is the only Balkan state with an extensive state rail system, although “first-class” might be second-class on the Deutsche Bahn. Before departure, a group of Roma walked through the train peddling used paperbacks and souvenirs before being shooed away by the CFR conductor.

The train to Brasov takes two and a half hours and gradually ascends from the Wallachian Plain to the Carpathian Mountains, with stops at Ploesti and Sinaia. Ploesti is famous as an oil center which was Hitler’s only source of petroleum as the war wore on. It was bombed by the US in August 1943 in Operation Tidal Wave, which wrought great destruction but also resulted in heavy losses of B-24s. It’s still a functioning oil town.

After arriving at Brasov, I took an Uber to my modern Airbnb. My young driver was part Russian and spoke excellent English. I negotiated a return drive to Bucharest Airport so that I wouldn’t have to navigate several train connections. I like to eliminate travel worries whenever possible.

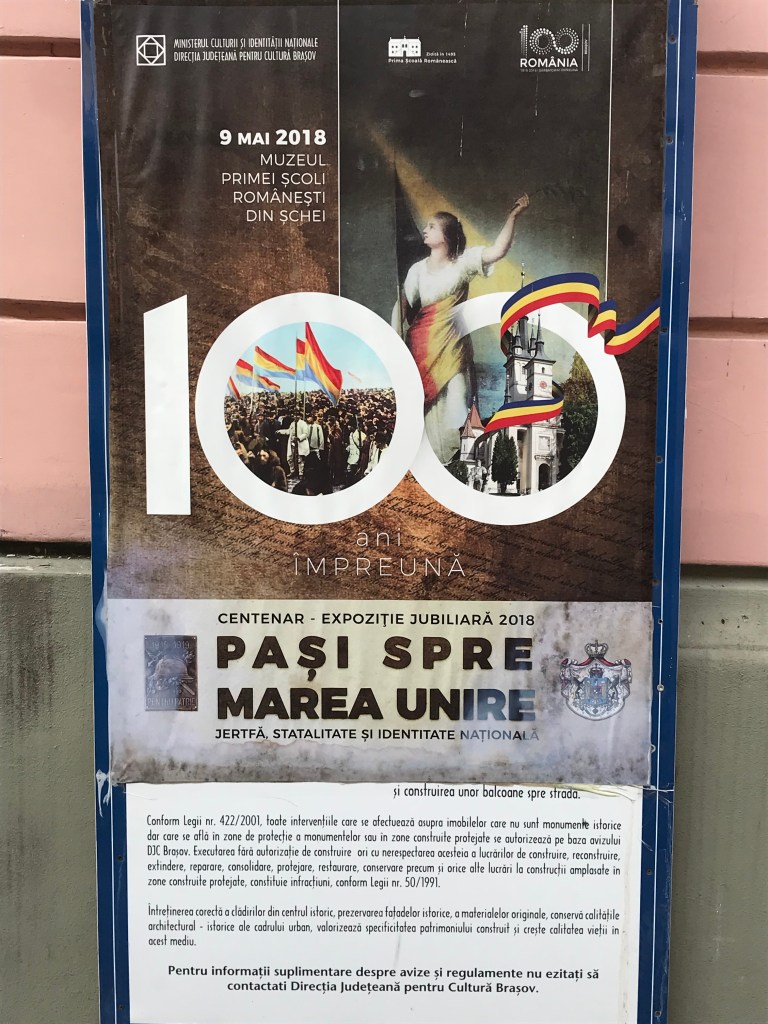

I walked into town to orient myself. Brasov was settled by Protestant Saxons and Hungarian Szeklers, who claim to be the direct descendants of Attila the Hun, during the centuries of Austrian and Hungarian rule. Up until 1918, it was a key component of the Hungarian Crown Lands, as they were formally known, before it was ceded to Romania in the Treaty of Trianon. The current president of Romania, Klaus Iohannis, is of Transylvania Saxon descent

The old town is going through a significant restoration. Its crown jewel is the Biserica Neagra, or Black Church, a Gothic church built in the 15th century.

View from my Airbnb with the Hollywood-inspired Brasov sign to the right (click to see)

Brasov tourist sign

The restored old town

The Black Church

Black Church clock tower

Cobbled street The next morning I met with Alex, my mountain biking guide for the next two days. We had interesting conversations during our ride up to the ski lift. He told me that before the 20th century ethnic Romanians were not permitted inside the Brasov city gates. It was an apartheid system. He also told me about the horrific brainwashing experiments that were conducted west of Brasov, in Pitesti, in the early ‘50’s under the direction of the notorious Communist Ana Pauker. About 750 students accused of hostility to Communism were incarcerated at the Pitesti Prison, where they were subjected to such sadistic physical and psychological terror that the term “horrorism” was coined. Fortunately, Pauker and her comrades were purged in 1952 and the horrors perpetrated at Pitesti were swept under the rug. You’ll need a strong stomach to read the accounts that were published after the fall of Communism in 1989. I noticed that young Romanians are well informed about the Communist era.

The trails were in great shape, though some of the higher ones were off-camber. There were some fun drops and great scenery. Alex said he’d been riding the trails for years.

Cross-country route

Trailhead

Above Brasov

Another view of Brasov

On the trail

View from high up After the first day tour, Alex took me to lunch at a traditional Romanian restaurant, which was included in the tour. He told me about some obnoxious Dutch tourists who kept exclaiming how “cheap” Romania was, which I’m sure he felt was demeaning. I might have thought that, but I wouldn’t proclaim it.

There was a large Kaufland supermarket across from my Airbnb so I picked up some provisions and made dinner at home. The ride was tiring, and I had to be ready for round two the next morning.

The next day I had an over the handlebars mishap and sustained a bad cut on my leg. I felt fine as we descended the mountain into Brasov, but we stopped by a pharmacy to get some bandages and antiseptic before lunch. Later that night I developed a headache and worried that I may have had a concussion so I gave Alex a call and he told me his brother-in-law was a radiologist and he secured an early morning scan for me at a private clinic. The tech was a true professional and the head MRI wasn’t bad. The total cost was $149, a fraction of the cost in the US. I was relieved when the doctor said there was no damage at all. My headache had also resolved. I was probably dehydrated. Since it was only a little after 8:00 am, there weren’t many places open yet, so I reluctantly went into a Starbucks, where I joked with the baristas about how awful their coffee was in the US. They promised that I would like theirs, and I did! By then, some of the old town cafes had opened, so I enjoyed a great breakfast.

Because of the MRI, I wasn’t able to make the tour of Castle Bran and other Dracula-related sites, so I went hiking in the nearby hills.

Nationalist graffiti in Brasov

Looks worse than it is

100th anniversary of the end of WWI

The imaging center

Alex and me

view from breakfast After checking out the next morning, I saw my driver waiting and we took off for the Bucharest airport, passing through some wild Carpathian countryside before reaching Ploesti, where we stopped for a coffee before ending up at the airport for my flight to Kyiv.

Gypsy lumber wagon in Transylvania I spent almost a week in Romania and had a fascinating visit. I’d like to explore other areas of this unique country in the future. It’s an accessible destination for North American travelers given the widespread use of English among the younger generation and the excellent food and wine.

-

Bucharest: August 16-19, 2018

Flights in the Balkans and Eastern Europe were quite inexpensive in late summer of 2018 and the easiest way to travel. After checking through passport control, I headed outside to meet my Uber driver for the ride into central Bucharest. My passport was filling up with new visa stamps since none of the countries I visited after Slovenia were in the Schengen Zone.

The drive from the airport revealed a much different cityscape than the other Balkan capitals. Monumental boulevards on the Parisian model lined with parks and impressive palaces and apartment buildings led to the central part of this city with over 2 million residents.

The Romanians are descended from the Dacians and Wallachians and like to consider themselves “an island of Latins in a sea of Slavs”, with the exception of their long-time nemesis, the Magyars of Hungary. They speak a Romance language, but, given their geographical isolation for centuries, it barely resembles Spanish or Italian. They like to say they’re the descendants of the Roman Emperor Trajan and his V Legion, thus the popularity of the male name Troian. They manufacture a car called the Dacia, which is now owned by Renault and quite popular in Southern Europe.

My Airbnb followed the usual pattern: a beautiful apartment inside an old 1920’s building. I was within walking distance of the historic core and around the corner from a Brutalist-style Intercontinental Hotel, which was erected during the Ceausescu regime, about which we will elaborate later.

Bucharest boulevards

Bucharest Airbnb

Kitchen

I walked to the old town for dinner at Caru’ cu bere and sat at the bar. The charcuterie was excellent, along with the local wine.

The next morning I walked a few blocks to meet Alexandru, my guide for the architecture tour of Bucharest. We were joined by a young engineer visiting from Beirut. Alexandru had recently graduated with a degree in architecture, but was planning to move to Germany in search of greater economic opportunity. His grasp of Romanian history and politics was as impressive as his architectural knowledge.

Bucharest has an amazing variety of architectural styles, from Beaux Arts to Romanian Revival. We also visited some superb murals before heading to the government sector and the old town.

Moorish style rehabilitation

Art Nouveau residence

Romanian Revival building Unlike its neighbors, Romania managed to stave off the Turks and eventually became a tributary state, paying the Ottomans to leave them alone. Vlad Dracul, the inspiration for Dracula, gave the Turks a particularly rough time in the mid-15th century, famously impaling thousands of the Sultan’s troops. Consequently, there are few Ottoman buildings remaining.

After securing full independence in the late 19th century, the Romanians recruited a German Hohenzollern prince to be their king, Carol I. His son, Ferdinand, succeeded him as king and oversaw a major improvement in the lives of his subjects. His wife, Marie, was particularly well loved for her philanthropy.

Equestrian statue of King Ferdinand

Royal Palace

palace facade Alexandru then took us across the main square to see some of the Communist-era buildings, including the former headquarters of the Securitate, the notorious Communist secret police. Alexandru told us that if you were taken there, chances were good you’d never emerge alive. The Romanian Institute of Architects built a modern glass addition over the infamous building. The former Communist Party headquarters, from where the last dictator, Nicolae Ceausescu, fled after a massive crowd began booing him in December 1989, was actually built in the Fascist style in the 1930’s. For those with an interest in the macabre, the trial and execution of Ceausescu and his equally hated wife, Elena, can be viewed on YouTube, as can the execution of wartime leader Marshal Ion Antonescu 43 years earlier.

The balcony where Ceausescu made his final speech

The former PCR headquarters in Stripped Classicism style

Former Securitate headquarters From here we walked over to the old town to view some Orthodox churches and other prominent buildings. One building was the sole skyscraper of pre-war Bucharest. After Romania left the Axis in 1944 and joined the Allies, the Luftwaffe tried to bomb the building, which was being used as a radio station. They missed and destroyed the National Theater instead.

The Art Deco skyscraper targeted by the Luftwaffe

Pre-war Art Deco buildings

16th century Orthodox church

Beaux-Arts Romanian National Bank established by King Ferdinand

Old town with Romanian National Bank dome in the background Alexandru walked us through the architecture faculty where he studied on the way to lunch. I enjoyed the tour and history lesson so much I treated Alexandru and the Lebanese engineer to a traditional lunch in old town. Alexandru shared that he had recently been in an anti-government protest and had been tear-gassed. He made the comment that the current government were recycled Communists in Italian suits. A few years later, a reform government sentenced the former Socialist Party chairman to prison for massive corruption. He also told us that the Soviets deported 500,000 Romanians to the Soviet Far East and Siberia and replaced them with ethnic Russians and Ukrainians, which accounts for the fair hair and light eyes seen in the city. Regarding the gypsies, now known as Roma, he joked that most of them had left for Western Europe since they could be guaranteed a minimum income of €800. He emphasized that Romanians cringe when tourists ask about Dracula, so I refrained from bringing it up.

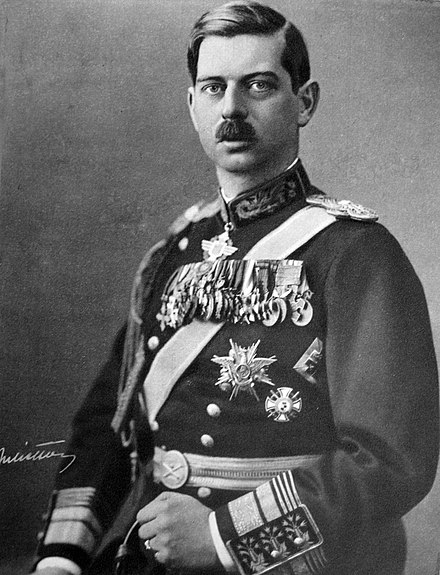

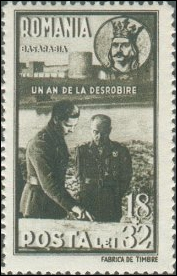

The next morning I joined another tour hoping to see some additional monuments and sites. Our tour guide was particularly infatuated with the sex life of the much-loathed King Carol II, who suffered from priapism and was constantly on the prowl. He went through two wives and carried on an affair with Madame Lupescu, whose Jewish origins weren’t popular in prewar Romania. Carol was deposed and exiled in 1940 when General Antonescu and Horia Sima established the National Legionary State. Romania went on to join the Axis and invaded the Soviet Union in summer 1941 as Hitler’s partner. The Romanians lost 300,000 troops during the invasion and were crushed at Stalingrad. Before long, King Michael, Carol’s son, abolished the Antonescu regime and changed sides. Stalin let him remain as King through 1947, when he was ordered out of the country and the full rigor of totalitarianism was imposed by the Party.

King Carol II

King Michael

King Michael and Marshal Antonescu on commemorative stamp

The Neoclassical Athenaeum

Main boulevard leading to the residential quarter

The Commercial Bank building Few countries in Europe have as interesting a history as Romania. I’d been looking forward to visiting it for years. During the 20th century it went through a victorious WWI when it regained Transylvania from Hungary, the Dobruja from Bulgaria and Bessarabia from the USSR, only to lose most of it within 25 years. Its people suffered under a corrupt king, a fascist dictatorship and a particular monstrous version of Communism, ending with the despotic rule of the Ceausescus. After the disastrous 1977 earthquake, the Ceausescus saw an opportunity to raze the historic area and its historic churches to construct their megalomaniacal Palace of the Parliament, the largest building in Europe. It’s now the seat of the Romanian parliament. It has to be seen to appreciate its enormity.

Palace of the Parliament

The nearby embankment

The Palace frontal view After checking out of my lovely rental, it was time to head to the Gara de Nord, Bucharest’s main train station, for the ride up to Brasov in the Transylvanian Carpathians.

Military recruitment ad in the Gara de Nord in the Latin Romanian language -

Plovdiv

The drive to Plovdiv was scenic, with the Rhodope Mountains to the southeast on the border with Greece. Igor was quite entertaining. He told me that vast amounts of war matériel disappeared into the mountains after the collapse of the Communist regime in late 1989. He hinted that his father knew where some of the caches were and volunteered that he had gone to the Turkish border during the migrant crisis of 2015 to prevent any refugees from entering Bulgaria. Atavistic hatreds persist in the Balkans. He drove me directly to my hotel and we agreed that he would pick me up after my two nights in Plovdiv to drive me to the Sofia Airport for my flight to Bucharest.

The innkeeper was gracious and showed me to my room, which was large and quiet. I decided to walk through the historic sections of this ancient city with roots in the 6th century BC. It was founded before the Greek Empire and claims that Philip of Macedonia was born there. It’s built on seven hills and was also a major Roman city, with abundant ruins.

Ancient street

Roman hilltop ruins

Plovdiv garden

Roman tomb

View of hills

Roman sepulcher Plovdiv also has some very good restaurants and bars for a city its size.

Old Town scene

Pedestrian mall lined with restaurants

1920’s building

Plovdiv City Hall The free tour of Plovdiv delved more into its classical history. We viewed some old Ottoman neighborhoods that retained their unique architectural charm. They ruled Bulgaria for 500 years, conquering it when it was the Byzantine city of Philippopolis, named for King Philip II.

For dinner, I chose the curiously named Hemingway’s! I was one of the first diners and the server asked if I’d mind delaying the mushroom course since the owner was en route with fresh mushrooms from his farm. Speaking of farm to table! The food and ambience were superb.

Caprese with burrata

Super fresh mushroom appetizer

Braised pork main dish The restaurant was next door to some Roman ruins.

The next morning I walked up Bunarjik Hill to view the massive Alyosha Soviet War Memorial. There was also a monument to Tsar Alexander III. On the way up I spoke to some young Israelis who were visiting during their military leave. They said that the flights from Tel Aviv to Sofia were cheap so they often travel here. I also spoke to a young German parkour enthusiast who was filming himself doing daredevil stunts.

Alyosha standing guard over Plovdiv

“Glory to the Heroic Soviet Army” After visiting Alyosha I headed back to the hotel, checked out and saw Igor waiting for me to take me to the Sofia Airport. Bulgaria is a country worth visiting.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.